Harry Geels: Five long-term challenges for the current banking model

This column was originally written in Dutch. This is an English translation.

By Harry Geels

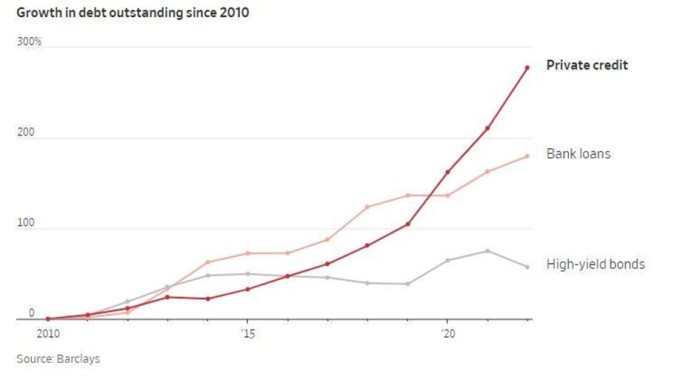

Companies, especially smaller ones, are raising more and more money outside the banks. The growth of private debt markets is rapid. Possibly even too rapid, the IMF believes. What other trends are gnawing away at banks' business models?

According to Stichting MKB Financiering, companies in the Netherlands received €5.148 billion in financing last year outside the major banks, a growth of 27% compared to the previous year. Due to increasing regulation, higher capital requirements and compliance obligations, banks are quickly withdrawing from the financing market for small and medium-sized businesses. The share of financing from the non-banking sector was 36% in the Netherlands at the end of 2023. Banks are increasingly feeling the competition from private markets. And that is a good development.

The current banking model is under pressure in various ways, not only due to the rise of private financing. Big Tech, leasing/renting, fintech and digital money also pose challenges (in the longer term). Let's go through them one by one, with an emphasis on the private financing markets.

1) The growth of private markets

The growth of private financing or credit has been much faster than the growth of bank loans in recent years. Banks provide fewer loans to SMEs because it costs them too much work and requires capital. The fact that private investors are now getting involved is positive for several reasons. It is good for innovation and competition in an economy that smaller companies can emerge and continue to grow. Moreover, there is leverage on the bank balance sheet. This increases procyclicality in the economy. In good economic times, banks tend to lend too much and in bad times too little.

Figure 1

Via the private markets, companies gain access to credit that is potentially available for much longer. Banks tend to request loans earlier and 'link' lending to other banking activities. In addition, private markets can bring more flexibility to loans, because they do not have to comply with the Basel guidelines. Banks are still a major competitor for private investors for large loans. Banks can finance themselves cheaply (with leverage) on the capital markets (in fact with an implicit government guarantee).

2) Big Tech

Big Tech has entered the financing and payment markets. For example, American customers of Apple Savings can receive 4.4% interest on their savings accounts, much more than the interest offered by American banks. Apple also has Apple Card and Pay. Amazon Web Services (AWS) serves dozens of financial companies, including Aon, Capital One, Carlyle, Nasdaq, Pacific Life and Stripe. Google Pay allows users to make digital payments via their mobile devices or online. We are only at the beginning of Big Tech's digital financial services.

3) Leasing/renting

The trend to rent more expensive products such as cars, telephones and kitchen appliances is increasing rapidly. Renting has advantages: one does not have to make a large upfront investment and the supplier is responsible for the maintenance and lifespan of the product, which is potentially more sustainable. Renault Bank, for example, links the (monthly) rental of the car to credit cards and current accounts. This form of service involves a banking license or a 'white label bank'. The big difference is that a company like Renault is 'in the lead', not the bank.

4) Digital money

It will take some time, but central banks will also start offering digital money, a trend that we should monitor with suspicion, because such money is potentially programmable. Citizens (and later possibly companies as well) will then receive two bank accounts, one with commercial money (from the 'ordinary' bank) and one with public money via the central bank. Initially, central banks want to offer this service on a small scale ('to make the financial system more stable'), but 'mission creep' will undoubtedly lead to a much wider application of digital money.

5) Fintech

An IMF paper entitled 'Is fintech eating the bank's lunch?' concludes that fintech potentially creates competition for banks and is potentially disruptive (and can affect banks' profit margins), but that it also has advantages. Banks themselves are also investing in technology. The main question will be whether traditional banks can switch quickly enough and whether existing activities and overhead do not get in the way too much. In any case, it is justified to say that fintech will further shake up the landscape of financial products.

The bank of tomorrow?

Traditional banks are among the most privileged sectors in the economy. They have the right to potentially very profitable money creation and can take risks (via leverage on the balance sheet, which is the envy of even the most offensive hedge funds), all under the cover of central banks and governments. It is good that there are social trends that challenge banks. However, it is likely that the banks will not easily give in thanks to a powerful banking lobby, helped by the fact that the government uses banks for its policy.

That is why I present an even bolder forecast: some of the banks will work even closer with the government in the coming decade, while another part will merge with Big Tech (which potentially produces very powerful corporates).

This article contains a personal opinion from Harry Geels